"America is a lecture-hall on a very extensive scale. The rostrum extends in a straight line from Boston, through New York and Philadelphia, to Washington. There are raised seats on the first tier in the Alleghenies, and gallery accomodations on the top of the Rocky Mountains....The voice of the lecturer is never silent in the United States."

Edward Peron Hingston, The Genial Showman. 1870

“Today, large numbers of ‘orders’ and clubs of all sorts have begun to assume. in part the functions of the religious community. Almost every small businessman who thinks something of himself wears some kind of badge in his lapel. However, the archetype of this form, which all use to guarantee the ‘honorableness’ of the individual, is indeed the ecclesiastical community.”

Max Weber. ‘”Churches” and “Sects” in North America: An Ecclesiastical Socio-Political Sketch’ .1985

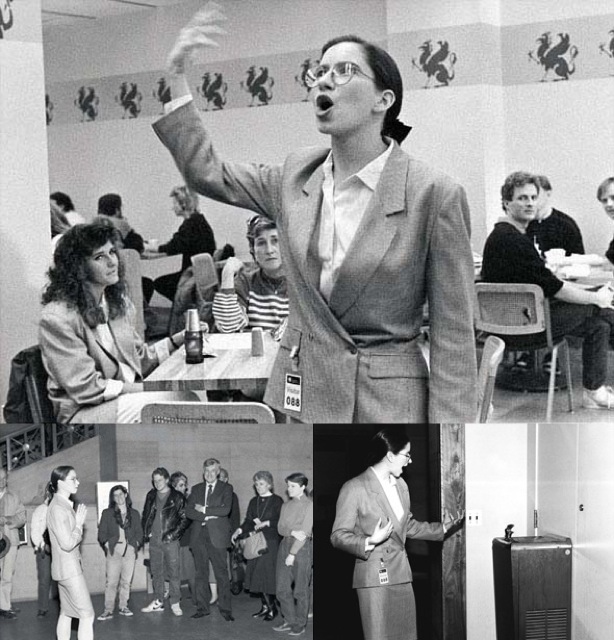

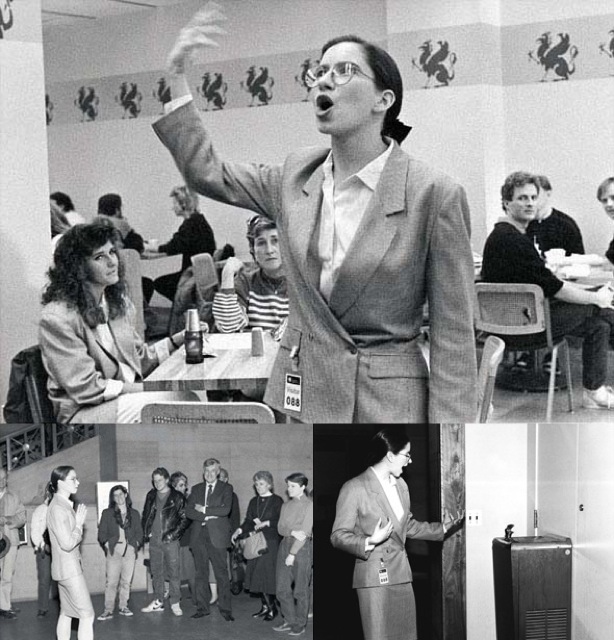

Noami Wolf, la célebre autora del libro “El Mito de la belleza” cuya tesis central es la de que la belleza es un mito inventado por la sociedad patriarcal para someter a las mujeres, se dirige desde el púlpito de una iglesia a sus feligreses. En ésta ocasión el pastor secular ha cedido su puesto a la vocera de la Tercera Ola del Feminismo. El tema de la puesta en escena y el discurso crematorio puritano es en éste caso específico, es el de que la belleza es un mito creado por la industria de las dietas, la cirugía plástica y los cosméticos. No importa que nuestra atractiva y rolliza activista sea adicta a los cosméticos y las interminables sesiones en la peluquería, tal como se puede apreciar en los primeros planos y por la fama que la precede en el medio feminista (1)

Pero aunque la hipocresía sea hermana del discurso “político”, detengámonos más bien en la representación y la acción dramática. La arenga de Wolf, en un espacio construido para el ritual religioso quisiera ser casual, pero no podría serlo por más empeño que le pudiéramos poner. Su “misa cívica” es un viaje en el tiempo hacia la Nueva Inglaterra del siglo XVII; hacia las arengas puritanas de los peregrinos contra el placer, el mundo, la belleza y el ocio.

“Spiritual beauties are infinetly the greatest, and bodies being but their shadows of beings”

escribía el pastor-misionero de New England Jonathan Edwards hacia 1756 en su “The Beauty of the World” y no nos resulta extraño que con un epígrafe suyo Michael Fried de inicio a su “Art and Objecthood” (1967) y que sus ideas sobre el concepto religioso de “gracia”, sean tan fácilmente aceptadas por la agendas neopuritanas minimalista y “política”.

La transposición del sermón de Wolf es tan fresca y encaja tan perfectamente en la iglesia en la que se lleva a cabo, que reproduce incluso la dinámica del “Call and Response” de la misa pentecostal en la cual las llamadas del pastor al Espíritu Santo son respondidas por los vivas de los feligreses.

Hoy en día asistimos a la transformación del Arte en la nueva forma del Espíritu Santo de la Religión Civil y de la de la Teología Pública (2). Aquí, el discurso puritano del vicario es heredado por el “artista-activista-pastor” predestinado. En la nueva religión los mecanismos de salvación pasan por el Arte y no por otra instancia. Si alguien quiere recrear una plegaria dominical en la Iglesia primitiva pentecostal, solo tiene que asistir a un performance de Andrea Fraser o una Lecture/Mass de Naomi Wolf. Pero si no se tiene la oportunidad de viajar, un acto “artístico-activista” en la Tadeo o una lección de moral de Tania Bruguera nos pueden trasladar a versiones hispanizadas de lo que podría haber sido una arenga puritana del siglo XVII.

El caso que aquí ya examinamos de la “misa” de Doris Salcedo y Víctor Laignelet, podría parecer un hecho aislado pero solo es el invaluable testimonio de un espacio que ha sido colonizado sin presentar la menor resistencia hacia las formas representacionales que prevalecen en la cultura dominante y las raíces religiosas sobre las que están construidas. La episcopalización del espacio universitario, así como del museo y las instituciones y los mecanismos de coersión temática que usan para definir quién hace un arte correcto y quien no, han hecho de éstos espacios, más que espacios donde se imparte educación, espacios donde se regula la obediencia del joven artista hacia la institución, del mismo modo que el comportamiento social de los individuos era controlado por los pastores con el dedo en la Biblia. Ya Benjamin Franklin en su Autobiografía hace la diferencia entre educación y regulación sectaria:

Had he been in my opinion a good preacher, perhaps I might have continued, notwithstanding the occasion I had for the Sunday's leisure in my course of study; but his discourses were chiefly either polemic arguments, or explications of the peculiar doctrines of our sect, and were all to me very dry, uninteresting, and unedifying, since not a single moral principle was inculcated or enforced, their aim seeming to be rather to make us Presbyterians than good citizens. Benjamin Franklin. Authobiography. Part II. 1784.

El tema del Arte Político Contemporáneo es el mismo del Puritanismo: el control de la vida de los demás. El actor cultural es el nuevo Censor Morum. Todo esto cobra en el producto final una forma teatral y por eso es tan atractivo el campo que se abre a un estudio concienzudo sobre las raíces pentecostales del Performance político en casos como los citados y en sus derivados:

“There are a lot of churches that have women pastors; that is not just the Pentecostal churches. I’m sure you well know that there are women pastors in the Methodist church, there are women pastors in the Presbyterian church, there are women pastors in the Episcopalian church, there are women pastors in the Baptist church–I think the American Baptist church has ordained some women–there are a number of churches that would have women ordained.

Why do they do that? Well, there are a number of reasons. Some are historical: the Pentecostal church, from its inception almost, has had women pastors because in the main early on, it was generated largely by women. I think it was more experience-oriented than doctrinally-oriented. Consequently, women sort of led with that experience. There was not a strong theology; there was not a strong theological foundation to that movement at all. And, of course, from a more contemporary perspective, the modern foursquare movement was basically generated by a woman.”Pastor John MacArthur Jr. http://www.biblebb.com/files/macqa/70-10-6.htm

Pero así como el feminismo radical de Wolf parece estar encontrando de nuevo sus raíces en el púlpito del que habla el Pastor Mc Arthur, el Arte Contemporáneo parece estar encontrando por fin el medio al que pertenece por naturaleza. No los sindicatos, no la plaza pública, no los espacios donde se diseña la ley, sino las iglesias que son el espacio natural desde donde se diseminó la Compasión – ese ejercicio religioso que el Arte Contemporáneo decidió llamar Política – hacia los Museos, las Bienales, las Universidades y en general las Instituciones que trazan el camino correcto de la Cultura. El uso de la Iglesia como espacio del Arte Contemporáneo y de la arenga “política” se abre camino y no debemos sorprendernos, pues que es a esos espacios que este arte pertenece más que a ninguno.

Las ideas de Tom Miller, el encargado para la Liturgia y las Artes de la Catedral de Nueva York son claras. Miller le explica al corresponsal de Art 21 que la apertura de su iglesia hacia el Arte Contemporáneo se debe a que encuentra multitud de símiles entre ésta y la Teología de la Iglesia Episcopal a través de la forma de mayor prestigio moral que tiene la cultura: la Compasión.

“In the Episcopal tradition, incarnation is an important part of the doctrine, but it’s not just in doctrine, devotion, or liturgy. So, it is part of tradition to think that everyone in the world, not just church people, are created with this creative impulse. Artists live to investigate and understand the world and sometimes advocate”

Hrag Vartanian: What role does the concept of “compassion” have within that mission?

TM: Compassion involves awareness (or consciousness), enquiry, and empathy (or compassion). For us, compassion finds a powerful exemplar in Jesus, who seemed always to be aware, or to be striving to know the reality of peoples’ lives and his own identity, for that matter. He then inquired about what people needed, what was lacking in their lives, when it wasn’t already apparent. And finally, he undertakes his own “passion” and makes it “compassion” by offering his passion for the good of the world and the illumination of human beings then and down through history.

Now, you can take the Jesus bits out and I think my original statement is true and it informs our criteria for art in the Cathedral. Does the work raise our consciousness about the (or a specific) human condition? (And condition can sometimes be simply the beautiful and sublime.) Does it assist us to contemplate the reality of the human condition (or conditions)? And in a way we frequently cannot control, does the awareness and contemplation lead us to the deeper and more profound place of our integrated being in order to offer ourselves to make a difference or at least to be in solidarity with the human reality of the condition?

The formulation the Cathedral often uses is to say we are a place where liturgy and the arts lead us to discourse and on to advocacy. Again, because art can move us beyond the narrow world of dogma and church tradition, it is an invaluable part of our mission. Art can help us go where our set ways might keep us timid.

HV: Who are some of the artists that have participated in the art programming at the Cathedral?

TM: We’ve had any number of artists. In the past, Bill Viola did a piece here. We’ve worked with Jenny Holzer, Michel Ostlund, Pat Lipsky, Thomas Albrecht, Barry Moser, Frederick Franck, Gregg Wyatt, a lot of others.

HV: Why do you feel it is crucial to continue St. John’s inclusion of visual art within its programming?

TM: To some extent, I think the answers above at least begin to answer your question here. The Cathedral is blessed with fantastic permanent “sacred art.” There, glass, stone, wood, and the architecture itself are glorious, but art and the imagination are alive, and although the sacred arts elicit a lively response from most people, we would be missing a huge asset by not making art in the Cathedral, through contemporary artists, through artists-in-residence, and by keeping the awareness, enquiry and empathy (or compassion) part of our life.(3)

Por otro lado, el Institute of Art, Religion, and Social Justice inauguró en noviembre pasado su primera exposición que no podía tener otro nombre y otra idea diferente:“Compassion”. La presentación de su curador A.A. Bronson, director del mencionado instituto, lejos de parecer retórica, nos señala con precisión el sitio natural de la noción de Política que manejan artistas, curadores, educadores y en general la Corporacion del Arte Contemporáneo, sitio natural del que se exilió por cuenta de los malabarismos retóricos del postestructuralismo .

“In today’s shifting political, economic, and ecological landscape, the need for compassion has never been greater, compassion understood as mutual interdependence, knowledge of self and others, and concern for human flourishing. This kind of compassion requires seeking to know all aspects of human reality, being open to truths beyond our everyday experience and embedded in it. Artists often awaken compassion most profoundly. They form our imaginations such that we can envision our interconnectedness in ways that mere didacticism cannot achieve.

Compassion used the buildings of Union Theological Seminary to create a kind of pilgrimage. The works were situated in various locations to create a tour of this remarkable and often overlooked historic complex.”

Y aunque faltan muchos de los artistas más especializados en el tema de la compasión. La presencia de los que se presentan es elocuente:

“Alfredo Jaar’s Embrace (1995), from his Rwanda series, greeted the visitor in the Hastings lobby. Scott Treleaven was featured in the James Chapel with black and white photos from Cimitero Monumentale (2009). Marina Abramovic’s video 8 Lessons on Emptiness with a Happy End (2008) shared the Narthex with Yoko Ono’s Whisper Piece(2001). Terence Koh’s invisible installation was located in the Refectory, with its 40-foot ceiling and massive stone fireplace, nearby. If the visitor strayed to the other end of the building, she might have found Bas Jan Ader’s iconic image I’m too sad to tell you in the Burke Library, echoed in the plaintive chant of Michael Bühler-Rose’s liquid ritual I’ll Worship You and You’ll Worship Me (2009), which could be found in the upper reaches of the Rotunda. Chrysanne Stathacos’ Rose Mandala Mirror (three reflections for HHDL), also in the Rotunda, was originally created in honor of the Dalai Lama. While circumnavigating the cloisters that link the various spaces of the seminary, further works by Gareth Long and Paul Mpagi Sepuya could be found.”

The Institute of Art, Religion, and Social Justice was founded under the auspices of Union Theological Seminary to explore the relationship between contemporary art and religion through the lens of social justice. http://artreligionandsocialjustice.org/htmllive/index.html

————————————–

(1) Camille Paglia así se lo cuenta nada más y nada menos que a Playboy, la revista que ninguna feminista que no fuera Paglia, se atrevería a visitar:

“PLAYBOY: How about Naomi Wolf?

PAGLIA: Daddy’s little girl? Her Rolodex feminism?

PLAYBOY: Rolodex feminism?

PAGLIA: She always says to [pantomiming get a Rolodex and keep the names of all the women we know and we’ll be able to call them up and get a job and we’ll have women power. [Cringing She is so naive. I can’t stand her. She’s hopeless.

PLAYBOY: Don’t you acknowledge the existence of what Wolf describes in her book The Beauty Myth: a culture manipulated by Madison Avenue that trains women to associate their self-worth with their looks?

PAGLIA: That’s hilarious. Wolf says we shouldn’t succumb to an this bullshit, but she spends four hours having makeup applied before her TV appearances and–I’ve heard–can’t pass a window without looking at herself I mean, look at her hair! It is the only thing that gave her cachet when she came onto the scene. Her book was one of many tired feminist books. What distinguished her was her hair; she owes everything to that hair. But then she cut it off. She’s trying to find a more serious persona. She’s looking for a hairstyle. It’s horrible. It’s embarrassing.”

(2) M.Marty .”Civil Religion in America”. 1967

(3)FLASH POINTS: Do artists have a social responsibility?http://blog.art21.org/2009/07/28/art-compassion-ny-cathedral/