“The sense of all this produc’d different emotions in me, viz., a delightful Horrour, a terrible

Joy, and at the same time, that I was infinitely pleas’d, I trembled.”

Joy, and at the same time, that I was infinitely pleas’d, I trembled.”

John Dennis, Miscellanies in Verse and Prose. London, 1693

“A leisure class, which exists on the

labor of others, which has no function to perform in society except the

clipping of investment coupons, develops ills and neuroses. It suffers

perpetually from boredom. Their life is stale to them. Tasteless, inane,

because it has no meaning. They seek new sensations, new adventures

constantly in order to give themselves feelings.” Michael Gold. “Gertrude Stein: A Literary Idiot.” 1935

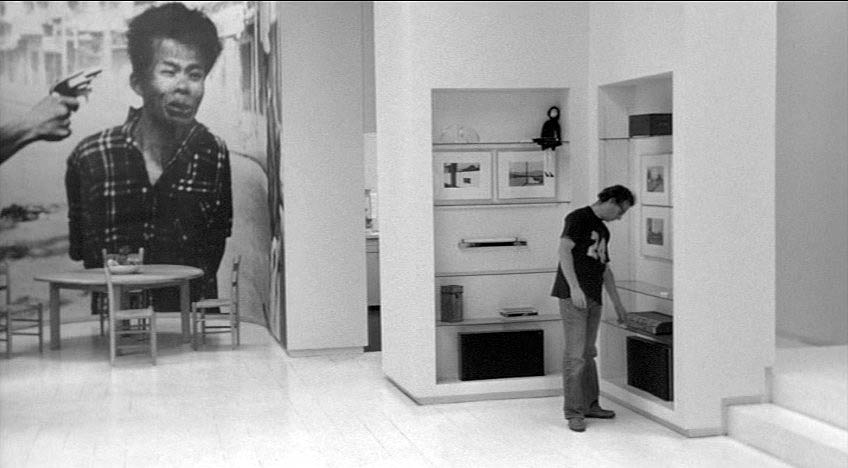

La residencia del cineasta Sandy Bates en el filme “Stardust Memories” de Woody Allen prefigura en 1980 lo que será el nuevo Interior burgués y la decoración de interiores contemporánea; Allen ha logrado redefinir el concepto de “decoración por la decoración” en favor de un nuevo tipo de “decoración política y de denuncia”, convirtiendo éstos dos conceptos complementarios en los elementos claves de un nuevo arte de género que puebla espectacularmente las paredes y complementa de modo original el amoblado minimalista y sobrio, creando una nueva forma de confort con guiños de decoración no convencional que influirá de gran manera el hábitat de la oficina, el hall y los corredores corporativos y el museo mismo.(1) Es previsible que en un corto plazo, en lugar de un Orgasmatrón ( Woody Allen “Sleeper”, 1973), se puedan mostrar a los visitantes hologramas animados de víctimas de mutilación, desplazamiento o incluso hacer “slumming” por barrios pobres sin moverse de la casa.

Si en el espacio de Bates observamos magnificada la célebre imagen de Eddy Adams de 1968 de la guerra de Vietnam donde el policía Nguyen Ngoc Loan ejecuta frente a una cámara de cine a un prisionero del Vietcong, en el espacio contemporáneo se ha dado, después de 27 años, un gran salto cualitativo en la decoración del interior. Ya no tenemos imágenes provenientes del periodismo, sino imágenes recolectadas (a menudo apócrifas), creadas o manipuladas por el artista “war profiteer” en su nueva dimensión de decorador de interiores. Con una supuestamente grande y blindada reputación de conciencia y sensibilidad tras de si frente al dolor de los Otros y a las víctimas de la guerra y a la vez con un gran talento decorativo, cumple con lo que Robert Smithson llamaba la “lobotomización política” de la obra dentro del espacio burgués en favor del confort:

“A work of art when placed in a

gallery loses its charge, and becomes a portable object or surface

disengaged from the outside world. A vacant white room with

lights is still a submission to the neutral. Works of art seen in such

spaces seem to be going through a kind of esthetic convalescence. They

are looked upon as so many inanimate invalids, waiting for critics to

pronounce them curable or incurable. The function of the warden-curator

is to separate art from the rest of society. Next comes integration.

Once the work of art is totally neutralized, ineffective, abstracted,

safe, and politically lobotomized it is ready to be consumed by society.

All is reduced to visual fodder and transportable merchandise”.(2)

El efecto dramático de la obra de denuncia, siguiendo los mecanismos

de percepción del cerebro contemplados dentro de la estética de la

tragedia clásica, se esfuma después de un breve lapso de tiempo, siendo

ésta la razón fundamental de porqué los efectos del arte político sobre

la conciencia colectiva no son más que una ilusión efímera de rebelión

dentro de las estrategias, esas si a largo plazo, de propaganda de

mercado y reafirmación de su naturaleza decorativa. Tal y como lo

describe Hume, el drama es relegado después de unos minutos, o unas

horas en el caso del museo o la Bienal, al olvido:

It seems an unaccountable pleasure,

which the spectators of a well-written tragedy receive from sorrow,

terror, anxiety, and other passions, that are in themselves disagreeable

and uneasy. The more they are touched and affected, the more

are they delighted with the spectacle; and as soon as the uneasy

passions cease to operate, the piece is at an end. (3)

La obra pasa a esa otra cosa que es el confort dictado por la escala arquitectónica. La obra es, en términos de Benjamin des-realizada, despojada del agobio de poseer un uso concreto, en éste caso un uso político. (4) Entonces la ilusión delirante del espacio de toma de conciencia es reducida a lo que es realmente. Decoración pura.Carlos Salazar

(1) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VvLm-w23UbE

(2) The Writings of Robert Smithson, edited by Nancy Holt, New York, New York.

University Press, 1979

(2) It seems an unaccountable pleasure, which the spectators of a well-written tragedy receive from sorrow, terror, anxiety, and other passions, that are in themselves disagreeable and uneasy. The more they are touched and affected, the more are they delighted with the spectacle; and as soon as the uneasy passions cease to operate, the piece is at an end. One scene of full joy and contentment and security is the utmost, that any composition of this kind can bear; and it is sure always to be the concluding one. If, in the texture of the piece, there be interwoven any scenes of satisfaction, they afford only faint gleams of pleasure, which are thrown in by way of variety, and in order to plunge the actors into deeper distress, by means of that contrast and disappointment. The whole art of the poet is employed, in rouzing and supporting the compassion and indignation, the anxiety and resentment of his audience. They are pleased in proportion as they are afflicted, and never are so happy as when they employ tears, sobs, and cries to give vent to their sorrow, and relieve their heart, swoln with the tenderest sympathy and compassion.

David Hume. Of Tragedy. Essays Moral, Political, and Literary (1742-1754)

(4) By bestowing a ‘connoisseur’s value’, rather than a ‘use value’ on objects, the collector ‘delights in evoking a world that is not just distant and long gone but also better –a world in which, to be sure, human beings are no better provided with what they need than in the real world, but in which things are freed from the drudgery of being useful’.

Walter Benjamin, ‘Paris: Capital of the Nineteenth Century (exposé of 1939)’, in Rolf Tiedemann (ed.), The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA and London, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999) en Charles Rice. Rethinking Histories of the Interior.The Journal of Architecture, vol 9, Autumn 2004